Turbulent Years

Gli anni 70 vedono l'emergere di molti nuovi talenti, tra i quali Shyam Benegal, Mani Kaul, Anand Patvardhan, Tapan Bos, Suhasini Mule, che mostrano un approccio innovativo e vitale nelle loro opere. Gli stessi anni, tuttavia, registrano un contaccolpo traumatico sul documentario indiano per il bavaglio imposto ai mass media dall'Emergenza del 1975. Lingua: inglese

THE INDIAN DOCUMENTARY (5)

Turbulent Years

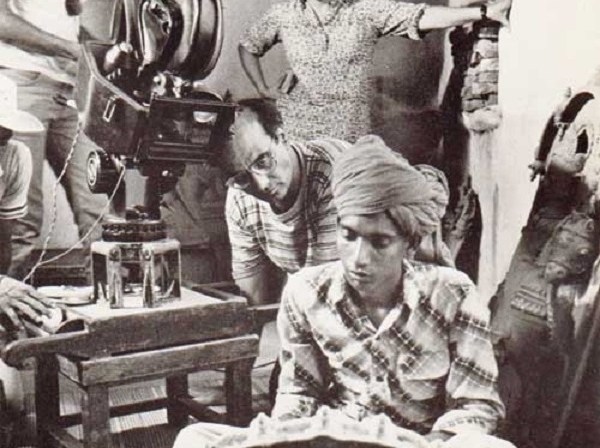

The 70s were both the best and the worst of years. Best, for the exciting new talent that appeared on the documentary scene bringing in fresh energy, radical outlook and innovative technique, notable among them Shyam Benegal, Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani, Vinod Chopra – the last three being alumni of the Film Institute, Pune. Worst, for the trauma caused by Mrs. Indira Gandhi's Emergency that stifled much of the creative impulse and the equally barren period of the Janata party rule, remarkable only for its ambivalence. More of these later.

Shyam Benegal who shot to sudden fame with his first feature film Ankur (1974) had begun his career with the well-known advertising agency, Lintas. He worked his way up from scripting ad films to making them himself. He had also been a film buff and read a considerable amount of theoretical work on cinema before he made his first documentary, A Child of the Street (1967) about juvenile vagrancy. It traces the traumatic experiences of a nine year old boy in a metropolitan city, his search for parental love and shelter before he ends up in a rehabilitation centre. The film had urgency, compassion and sociological concern. For a first film, Benegal also used his camera with surprising skill.

His next film Close to Nature took us to the tribal areas of Madhya Pradesh, providing a kaleidoscopic view of tribal life at different times and in varying moods – worshipping their gods, singing and dancing as dusk fell, bargaining in the marketplace, living in the ghotul (an institution where young people live together). It was a tricky film to make and required greater involvement and rapport with the subject. Unfortunately, Benegal failed to achieve this. One wishes Benegal had put to better use the words of Verrier Elwin with which he ends the film: "We must help the tribals to come to terms with their own past so that their present and future will not be denied from it, but be a natural evolution from it... we must not impose our own ideas on them. We must not create a sense of guilt by forcing on them laws that they do not understand and cannot observe".

Nevertheless Close to Nature was way ahead of Films Division's scores of films on tribal life where the district officer gets them to parade before the camera. (Perhaps an exception could be made of Prem Vaidya's Man in Search of Man on the tribals of Andaman and Nicobar Island.) Indian Youth: An Exploration, as the name suggests, was Benegal's attempt to understand the problems of modern Indian youth, both urban and rural, at various social and economical levels. Here he is clearly more at home than in the world of the tribals – eschewing a didactic approach, he presents a panorama of quick, flashing episodes, of several young people as they struggle through a fast-changing world, so different from the world of their parents. Another film, Horoscope for a Child, on protein deficiency among growing children, succeeds in being much more than that. Woven around a taxi driver's family living in one of Bombay's numerous chawls*, we get acquainted with a whole way of life, thus experiencing the problem in a socio-economic context. Benegal later moved to a different genre, and made several films on Indian music, notably Tala and Rhythm, The Shruti and Graces of Indian Music, The Raag Yaman Kalyan. In a sense, this was pioneering work which found greater maturity and finer expression in Mani Kaul's hour-long Dhrupad.

Mani Kaul came over to documentaries after he had made three feature films, Uski Roti, Ashad Ka Ek din and Duvidha. His first documentary was The Nomad Puppeteers of Rajasthan, an area he knew well enough having been brought up there. Mani follows a troupe of puppeteers as they move from place to place entertaining and ekeing out a miserable living. An entire family is involved in entertaining and making the puppets which they carve out of softwood and then paint and clothe. To our dismay we discover that this remarkable art is on the wane with the easy accessibility of the moving pictures. What is even worse, the puppeteers now prostitute their art by enacting scenes from popular cinema where the puppets dance to the tunes of film songs. But it need not have been so. Mani carries out his argument with great force and urgency in his next film Chitrakathi.

Made for the Films Division, in a 20-minute format which proved hopelessly inadequate, Chitrakathi is about the folk artists of western India who narrate with the help of leather puppets. Mani takes us to the sleepy Konkan coastal village and introduces us to the family that has preserved this unique art for several centuries. Now it faces extinction because younger men would rather go to the city and earn a living there, than practise an outmoded art which holds no future. What happens to these men who migrate to the big cities? Mani Kaul presents a searing study in Arrival. To the city come men, women, fruits, flowers, vegetables, goats and sheep – all ready for consumption. It is the process of consumption/exploitation that forms the core of the film. In a collage of images held together by an engaging soundtrack we are shown the brutality and dehumanisation of city life. Perhaps the best part of the film is the scene in the slaughterhouse where Mani shows us the routineness of death – rows upon rows of slaughtered goats and sheep, all ready for human consumption. Because he refuses to sentimentalise, the effect is electric. Only once before have I experienced the same cold academic ferocity, in Franju's La Sang des Betes. Mani extends the slaughterhouse metaphor to labour-intensive areas where human beings are exploited and reduced to insignificant cogs in a giant, merciiess machine. The film raises more questions than it can possibly answer. That perhaps is its intention.

Dhrupad, 1982 Dhrupad, a 72-minute long film which features two famous masters, the Dagar brothers of Dhrupad school of Indian classical music, is truly a pioneering work in the sense that nothing quite like this had been attempted before. It not only captures for us, and posterity, the magical quality of the two great masters' voices, but provides a valuable clue to the evolution of their art with its beginning in tribal music; Mani Kaul puts forth the argument that tribal music had two aspects: one concerned itself with ritualistic hymns and the other related to changing seasons, as also birth, marriage, death, etc. While the folk music stayed in the villages, the ritualistic music evolved into classical music and moved to the courts. In a simple yet effective structure, the film opens on the historical monuments at Gwalior, Agra, Amber and Mandu to the accompaniment of veena* recital. It is in this setting that the great Ustad Zia Mohiuddin Dagar explains the intricacies of Dhrupad style. The concluding passage of the film is on a panoramic shot of Bombay as the music reared in the courts of princely states undergoes a subtle change in a vastly different, industrialised milieu. Shot with immense love and care for tone, texture and colour, it is a landmark film.

Unfortunately, Kumar Shahani has not been very active in the documentary field, but one still remembers his moving film on spastic children, A Certain Childhood (a Leela Naidu production). It was probably the earliest in-depth study on the subject. Abandoned, vagrant children was also the subject of Vinod Chopra's An Encounter with Faces which won him several awards, including nomination for the Oscar at the 51st annual AcademyAwards. In this film Chopra takes over where Shyam Benegal had left off: he examines the lives of these children who lead a dreary, loveless existence at a rehabilitation centre. Using no narration and letting the children speak for themselves, Chopra turns his film into an authentic document. A determined man can beat the system. Loksen Lalwani did. Working within the fusty Films Division (which he later left) Lalwani made a searching study of the lives of coal miners in Bihar in his film Burning Stone. Lalwani shows us the inhuman conditions in which the coal miners work and live. He also underscores the constant fear of the money-lenders and the shenanigans of the politicall trade union leaders. Lalwani's camera follows them to the pits – revealing their primitive safety measures and the unremitting misery and squalor of their hovels. The only place where they can seek oblivion and indulge in fantasies of a glorious future for their children is the cheap liquor shop. When asked why he chose to call his film Burning Stone, Lalwani replied, "I could have called it ‘black diamond' as coal is referred to... but for the miners it is a burning stone. It is burning in the depths of the earth like a volcano waiting to erupt..".

They Call me Chamar, Lalwani's next film, was reportedly based on a newspaper item, of a brahmin having married a Harijan* girl. Socially ostracised, he is driven to the bustee* of the chamars* who live by skinning dead animals. Vultures peck at dead carcasses as we approach the chamar bustee to meet our protagonists. Lalwani lets the couple alternately relate their story which forms a powerful indictment of a cruel social system. It is a pity a man of such strong conviction and social consciousness died so young. And now the bad news. The portents were all there but it was the suddenness of it which took everyone unawares. On 26 lune 1975, the President of India through a proclamation declared that "a grave emergency exists, whereby the security of India is threatened by internal disturbances". Mrs. Indira Gandhi, the Prime Minister, was more reasurring, "The President has proclaimed emergency. This is nothing to panic about". As always, the axe fell on the media – press, radio, television, film. The earnest, authoritative Vidya Charan Shukla took overcharge of the Information and Broadcasting Ministry from Inder Kumar Gujral. Soon after assuming office, Mr. Shukla went into action. What happened to the press, radio, TV and feature film industry is only too well known. Perhaps less known is the irreparable damage Emergency and men like Shukla did to the documentary film. Emergency highlighted the vulnerability of the government-controlled media— AIR [All India Radio], TV and Films Division. Mr. Shukla and his ilk instilled fear in every area of creative and organisational activity. And to use Mr. L.K. Advani's famous phrase, men began to "crawl when asked only to bend". Fear stalked the corridors of Films Division. "The largest documentary film unit in the world" was reduced to an impotent giant. In an atmosphere rife with suspicion and supression, 'seasonal' filmmakers and political adventurists jumped on to the gravy train. According to the White Paper on Misuse of Mass Media, a number of films including Agya Do Hukam Karo, Zimmedar Waris, A New Era Begins and Godmen of Ganges were purchased by Films Division on orders from the Minister, bypassing both the Film Purchase Committee and the Film Advisory Board. Crude propaganda, hastily churned out by Films Division, filled the screens of the country. Mercifully, people could not be forced to watch it. The pity and sorrow of it was that when Mrs. Gandhi was voted out of power and the Janata Party brought in, nothing but nothing changed materially. Although the government was new, the men who constituted it were not. No sooner did they get into power than they resorted to the same old game of revenge and reprisal. Mrs. Gandhi was declared persona non grata on AIR, Doordarshan [televisione nazionale] and Films Division. Once when a TV producer unwittingly allowed a documentary in which Mrs. Gandhi had briefly figured, he was summarily sacked. Worse still was the case of an FD documentary which showed a portrait of Mrs. Gandhi in the background. All prints of the film were ordered to be withdrawn from the national circuit. So much for the high-minded declarations of Mr. L.K. Advani.

Like the proverbial silver lining to the dark cloud, a significant development in the aftermath of Emergency was the political comment film. Credit for this should go to a young man, Anand Patwardhan [Patvardhan], who was more of a political activist than a filmmaker. He took to filmmaking to put across his socio-political views to a wider audience. Patwardhan got considerable media attention with his half-hour 16 mm black and white documentary Prisoners of Conscience on the condition of political prisoners in India before, during and after the Emergency. Another documentary on political prisoners was Utpalendu Chakraborty's Mukti Chai. Shot mostly with hand-held camera which gave it a certain sense of urgency, Chakraborty postulated that right from the Rowlatt Act to the proclamation of Emergency, the repressive forces have never really let the individual out of their grip. A more effective, well-made film was Gautam Ghose's Hungry Autumn which won its director a prize at Oberhausen. Taking off from actual famine conditions in 1974 in West Bengal, the film analyses the basic Indian agronomic situation, widespreaddestitution and its repercussions on rural and urban societies. In the investigative genre, a truly courageous film was the Tapan Bose [Bos]-Suhasini Mulay [Mule] film, An Indian Story, on the notorious Bhagalpur blindings and the whole pattern of police brutality in India. Anyone who has ventured to make an unsponsored film knows the hazards of raising funds. Even the eventual fate of such a film is uncertain as Tapan was to discover later. Bhagalpur blindings had hit the headlines when it was discovered that some policemen had forcibly blinded 34 under-trial prisoners by puncturing their eyes with a thick needle and then pouring acid on the wounds. Tapan Bose started off by interviewing three of the blinded men in Delhi and then went to Bhagalpur to finish the film. Needless to say, the authorities tried every trick to dissuade Tapan and uniformed policemen shadowed the crew throughout. To cap it all, the censors banned the film only to be saved by a court order. For the socially committed, independent filmmaker it is a tight rope walk. It would appear that the establishment takes sadistic pleasure in keeping him poised so precariously. Glossario:

A cura di |

B.D. Garga

In "Cinema in India", Vol. II, No. 2, April-June, 1988, pp. 32-36..