Seconda parte del quarto articolo che Iqbal Masud ha dedicato alla genesi del cinema popolare indiano. Al centro dell'attenzione è il cinema degli anni Sessanta che, nonostante un certo declino qualitativo, sarà ricordato per aver saputo cogliere la "visione cosmica" di un'antica cultura e la "visione bizzarra" delle forze che da essa stavano nascendo. Lingua: inglese.

GENESIS OF THE INDIAN POPULAR CINEMAThe Sixties: Separate Truces, New Battles - part two

The other films I am going to deal with are not unentertaining. Guide and Ganga Jumna have a resonance going beyond entertainment. They raise issues which are still vital and troublesome.

The Guide (1958), one of R.K Narayan's best novels, was made into a film by Vijay Anand in 1965 with music by S.D. Burman and main performances by Dev Anand and Waheeda Rehman. There was some controversy at the time whether the film interpreted the text - or at least its spirit - correctly. What I would rather do is to look at the novel and the film as separate but linked cultural artefacts. Both their separateness and their linking are important for an understanding of Hindi popular cinema.

Guide (1965)

Let us take a look at the novel. I reproduce a modified summary from the Thesaurus of Book Digests (195080) merely for the reason that it is serviceable: "The novel is about a tourist guide who is also an unwilling spiritual guide to others, because, uncontrollably, he seems to be 'guided' by the gods to serve a purpose larger than his own petty prefigurings can conceive. 'Railway Raju' is an adventurer who succeeds whenever he seems most to be failing and in the end is overcome by at least a temporary conviction that, unworthy as he may be, his life and deeds have an incalculable importance. Raju runs a book stall and food stand at Malgudi railway station, but soon neglects them to become a tourist guide to visitors.

This is the past Raju recounts to the villagers in an abandoned temple where he has taken refuge after his release from jail - a punishment for one of his adventures which had turned into a misadventure.

Raju discovers that he had acquired a reputation as a swami among villagers, largely because he has 'miraculously' persuaded villager Velan's (who becomes his most fervid devotee) sister-in-law to accede to a marriage thrust upon her by her family. When the villagers rely on him to rescue them from a persistent drought, he is forced to undergo a fast - to bring rain to their parched lands. The fasting spiritualises him sufficiently to make him aware of moral changes in his purpose for living, so that in the end, his resources depleted, he senses the coming of the rain.

Raju's whole life is thus an oscillation between the ingenuity that makes him win out and the susceptibility to defeat that brings him closer to wisdom. When he forges his mistress Rosie's name to a receipt for jewellery, he is jailed for two years but survives quite well there as a hanger-on to officials. He had won the affections of Rosie, from her husband, the art historian Marco, who had neglected her. As her impresario he had groomed her to become a famous dancer. His concern for money and success had driven a wedge between them and destroyed their relationship.

Even the recounting of his tale by Raju does not shake the faith of the villagers in him. Because he is unable to dissuade others from seeing him as vulnerable, Raju accepts his role of spiritual guide, giving up the life he has led.

Guide has attracted comparatively lesser attention from critics than Narayan's other works. Still, William Walsh (R.K Narayan: A Critical Appreciation) and Suresh

Raichura (essay on Guide in Major Indian Novels - Arnold - Heinemann, 1985) have done some excellent work on it. One vital point made out by Raichura is that Narayan eschews "the grandiose, the spectacular, the sententious Big Statement." This is the basic difference between the book and the film. The film has all the qualities specifically excluded by Narayan. Guide is not a didactic or political novel. "It contains a master-code of pre-social, anti-individualist ideology - that is, Hindu view of life." (Raichura). Cosmos, world and community are prior to the individual, the whole is affirmed against the atomistic or fragmented. It assumes a pre-literate, oral, largely peasant culture. This, of course, reflects on the ethos of the middle class writer who hankers for what Palme Dutt called "the comfort of some rock of ancient certainty."

D.S. Philip in Perceiving India has taken an interesting view of Narayan. He calls him a reinvented traditionalist. Narayan attempts to re-formulate tradition in a modern idìom. This leads to a reinforcment of traditional cultural image. In Raju the rustics see a need to build up a myth and believe it. For Narayan the human personality remains unchanged. This automatically forecloses any chance of a new man emerging.

The film Guide departs at many points from the book. It jazzes up the book's Rosie - a querulous, uncertain though attractive creature - to a glamorous star. Waheeda Rehman despite her charm makes Rosie a caricature. Dev Anand, however, renders the chameleon adventurer, Raju, fairly faithfully. But his apotheosis at the end becomes a colourful debate far removed from the perfect ending of the novel: "They held him as if he were a baby. Raju opened his eyes, looked about, and said, 'Velan, it's raining in the hills. I can feel it coming up under my feet, up my legs,' and with that he sagged down." To me that remains the neatest and the loveliest ending of any modern novel. The film has destroyed it.

And yet one must get back to the basic question: What's the vision of Guide, the film? As much as the novel it's the vision of the Hindu view of life, of the triumph of common-sense community ethics over individual love and ambition. You will find it in Raja Harishchandra, Mother India of the 50s and Zanjeer of the 70s. The attractive individuality of Marco, Raju, Rosie dissolves into dust in the abandoned temple. Guide is but a variation on one of the most persistent themes in Indian cinema.

The theme of individual discrepancy and communal collaboration surfaces very cleverly in Basu Bhattacharya's Teesri Kasam (1965). This perhaps should have gone under entertainment - I know of few better entertainment films in Hindi cinema. The song and dance item Paan khaiyo saiyan hamara [Amato, mangia il mio betel] is incomparable. One of the basic elements of the film is the recreation of the lost world of the travelling theatre - the world of nautanki-folk songs and rhymed Laila Majnu dialogue.

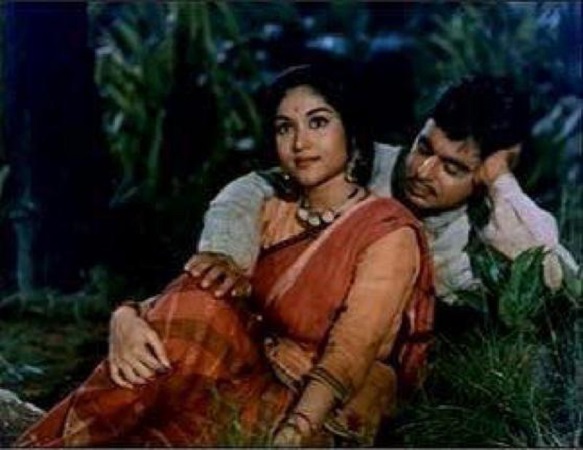

Tīsrī qasam (1966)

But Teesri Kasam is not merely a documentary piece. Nor is it a merely romantic drama of the love of a bullockcart driver (Raj Kapoor) for a travelling danseuse (Waheeda). Like Guide it becomes the working out of a relationship built on 'individualism' which smashes on the rock of reality - the life of the community.

The danseuse is an intruder in a rustic community. Unlike Rosie her roots are in this community but roots are no longer shackles for her. She is an artist and therefore permitted a lax code of conduct. But this code has its rubs. She can only have lax relationships, not permanent ones. Rosie hankered after such a relationship in Guide, the dancer here has nostalgic longings for it. But both are outside the pale. Therefore, the bullock-cart driver is doomed in his love, on two counts. First, his conditioning will come in the way of such a relationship - not directly perhaps but rendering it absurd in actuality.

A few moments of fugitive romance are all that's allowed. In Guide the relationship became intimate but that very intimacy soured it. Here the romance is even more fleeting. The community has planted, as it were, an internal censor in its members. Individual discrepancy is destroyed not by a tyrant but by the air, the ethos of the land.

But this vision can become suffocating. Naipaul has criticised Narayan's vision of Malgudi "because it fails to portray more forcefully the terrible poverty which is the dominant feature of Indian life. This is part of "the bizarrerie" of Indian life referred to in the Nirad C. Chowdhury quotation at the beginning of this artide. No comforting vision can quite wish away this horror and the other horror which it breeds - corruption.

Gangā Jamnā (1961)

Ganga Jumna on the surface is a variation of Mother India but it is an important variation. Mother India ended on a note of hope - we had all those community development workers of the 50s surrounding Nargis. On the other hand the hero's death (Dilip Kumar) in Ganga Jumna is the end of a saga of revenge - with no dawn. In that sense, Ganga Jumna is the true precursor of the anti-system dacoit films (right down to Dacait 1987). Even so obviously a non-dacoit film like Ketan Mehta's Mirch Masala (1986) has strong affinities with the Ganga Jumna ethos.

The variation is basically this. In Mother India it was landlord vs. peasant. Now it is a state-landlord-peasant triangle and it is a more menacing relationship because it is rooted in an ongoing conflict. Dilip Kumar plays the part of a peasant driven to banditry by police-landlord collaboration.

Gangā Jamnā (1961)

This is one of the first films where tutoring of witnesses and doctoring of justice is shown in realistic detail. This is manufactured reality but is close enough to lived experience. Actually it is a clash between two cultures: one culture which is based on law - "law is the circle which cements - man's civilisation," says the Inspector - confronts another culture spawned bv the victims of law. We are in a world far removed from Malgudi and we begin to see the limitations of the Malgudi vision. The scene where the dacoit brother (Dilip) meets the police man brother (Nasir Khan), is a precursor of million such scenes - and the best of them all. It is the dacoit's wife (Vyjayantimala) who immediately grasps that surrender would be death for a way of life and gets the dacoit out.

Ganga Jumna again has entertainment value - it has the best dialect exchanges and dialect songs of our films. But its real importance lies in going to the heart of a seemingly irreconciliable conflict in our culture.

Hrishikesh Mukherjee's Satyakam is like Ganga Jumna, suffused by religious and theatrical ambience. In fact its beginning - intrigue and romance in pre-1947 Princely India and its end - religious reconciliation in a bogus Malgudi kind of ambience - seem like a head and a tail attached to a creature of a very different colour. The heart of the film is the realistic depiction of the agony of an honest PWD engineer harassed and hounded to death. The power of the film lies in its 'bolts and nuts' depiction that is, the hurtingly credible presentation of the corruption and the enfeebling of the post-freedom Indian bureaucracy. The film is made memorable by a stunning performance by Dharmendra. Theatrical in places, this is realism at its best.

So when all reservations have been made about 60s cinema - its running down in quality and spirit - it will be remembered for two things: The way it captured both the 'cosmic vision' of an ancient culture and the'bizarre vision' of emerging forces in the same culture.

Note

Svāmī: lett. "possessore", "padrone"; "signore", "Signore"; "marito"; capo di un ordine religioso; titolo dato a un grande saggio o devoto.

Nautanki = navtankī: così viene chiamata in Uttar Pradesh una forma di teatro tradizionale che ha molti paralleli con forme simili sviluppatesi nell'India settentrionale e occidentale tra la fine del XVIII e l'inizio del XIX secolo.

Lailā-Majnūn: racconto popolare di origine araba che narra la tragica storia d'amore tra la bellissima Lailā e il giovane Qais, ostacolata dal padre di lei che costringe Lailā a sposare un altro, Ibn Salām. Lailā rifiuta di consumare le nozze e lo sposo, che l'ama, rispetta la sua volontà. Ibn Salām muore e poco dopo muore anche Lailā. Quando Qais, che nel frattempo è impazzito per amore (diventando Majnūn o "Folle"), apprende della morte dell'amata, muore a sua volta sulla sua tomba.

Iqbal Masud

in "Cinema in India", Vol. 1, No. 4, October-December, 1987, pp. 30-35.

Film citati nell'articolo (regista, anno, lingua):

Dacait (Bandito, 1987, Rāhul Ravail, hindi)

Ganga Jumna (Gangā Jamnā, Gangā e Jamnā, 1961, Nitin Bos, hindi)

Guide (1965, Vijay Ānand, hindi)

Mirch Masala (Mirch masālā, Polvere di peperoncino, 1986, Ketan Mehtā, hindi)

Mother India (1957, Mehbūb Khān, hindi)

Raja Harishchandra (Rājā Harishchandra, 1913, D.G. Phālke, muto)

Teesri Kasam (Tīsrī qasam, Il terzo giuramento, 1966, Bāsu Bhattāchārya, hindi)

Zanjeer (Zanjīr, La catena, 1973, Prakāsh Mehrā, hindi)

A cura di

Cecilia Cossio