Constitutional reform, limitation of the powers of the monarchy and the resignation of the prime minister appointed after the coup, Prayut Chan-ocha: these are the demands made by young Thai demonstrators, who have filled squares and streets across the country since February with their peaceful protests, adopting models similar to those already seen in Hong Kong.

We interviewed Prof. Edoardo Siani, researcher of the Department of Asian and North African Studies, to learn why this Southeast Asian country known as the Land of Smiles is instead going through such a tumultuous phase on a political level.

How did the 2020 protests in Thailand begin?

The current protests began in February following the forced dissolution of Future Forward, a political party critical of the military and with a strong influence on young people. The first demonstrations against the government took place in a few universities in Bangkok, later extending to other universities and schools. Interrupted in April due to the Covid-19 pandemic, they were resumed in full force at the end of July.

Taking advantage of the negligible impact that the health emergency has had in the country, they then spread like wildfire. It is estimated that tens of thousands of people took to the streets in cities scattered throughout the country. As part of the protests, the protesters raised strong criticism of the monarchy, breaking cultural taboos and challenging the injured majesty, a crime punishable by imprisonment. Unwavering in their demands, they demand the resignation of Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha, a new democratic constitution, and the reform of the monarchy aimed at limiting its powers as foreseen by the constitutional system.

Let's take a step back: how did such a tense political situation come about in Thailand?

To explain the current political situation, some Thais invoke an ancient prophecy. The founder of the present dynasty inaugurated the kingdom on 21 April 1782 at 6.54 in the morning. It was an auspicious moment, selected by the court astrologers as a guarantee of an extraordinarily powerful monarchy and army.

In 1932, the People's Party, a group of rebels, overthrew the absolute monarchy, promulgating the first constitution. Educated abroad and inspired by the ideals of the French Revolution, the rebels were part of a class of state officials who struggled to emerge in a system in which power remained centred around the elite. They heralded the new constitutional era as the advent of a golden age.

Those who demonstrate today argue that that golden age has not yet arrived. They contend that, just as predicted by the astrologers, kings and military continue to exert enormous influence on the country's politics - unusual for a constitutional monarchy. From 1932 to the present day, they point out, the army has carried out thirteen coups and Thai political and economic life continues to gravitate around the monarchy.

The current government, made up of retired generals, installed itself in power in 2014 with a coup against a democratically elected prime minister who was perceived as dangerous to the elite. In 2016, the army then managed the succession to the throne of King Maha Vajiralongkorn, who in turn requested and obtained amendments to the constitution drawn up by the military. The new king also took over the Crown funds, previously managed by the semi-state institution of the Crown Property Bureau. During the early years of his reign, several public monuments celebrating the fall of absolutism in 1932 were removed.

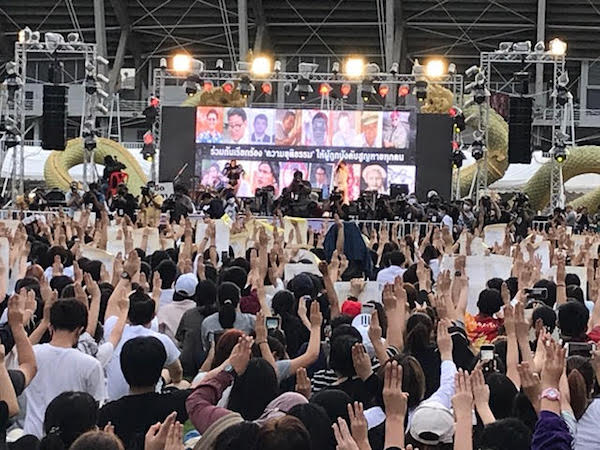

In the images of these protests, we see inflatable ducks and parades of young people with three fingers raised, the greeting borrowed from “Hunger Games”. But how are these events organised and who takes part in them?

Protesters mostly move by adopting the flash mob model already seen in the Hong Kong protests. They therefore meet almost daily, exploiting the potential offered by social media, in particular Twitter and Telegram. This way of organising the protests largely unannounced limits the risk of repression by the authorities. Previously, the police used water and tear gas cannons to disperse the crowds and in some cases made arrests.

Although this type of mobilization favours youth participation, demonstrators from various generations have shown their support on several occasions. The protest symbolism itself is innovative as it refers to the recent resistance movements in Hong Kong, to international pop culture, but also to the astrological language of the court, simultaneously addressing multiple audiences: international and Thai, young and old.

Examining the history of the country, protests and demonstrations seem to be fairly frequent events. Who are the young Thais inspired by?

The composition of the protests recalls the student movements of the second half of the last century. In particular, in the 1970s, students used to demonstrate against authoritarian governments and coups d'etat. Thai history tells of terrible massacres in which several young people lost their lives at the hands of military and paramilitary forces.

From an ideological point of view, the current protests are instead more attributable to the demonstrations of the those known as the Red Shirts, active from the early years of the new millennium until the 2014 coup. Mainly middle-aged people from the provinces, the Red Shirts objected to the military's meddling in politics and demanded a solid electoral system that guaranteed democratic participation. In addition, some groups within the movement cultivated strong criticism of the monarchy - a phenomenon then unprecedented.

The Red Shirts remain the largest political movement ever to exist in Thailand today. At the height of the protests in 2010, hundreds of thousands of protesters occupied Bangkok's financial centre for over two consecutive months. They were repressed by military fire in clashes in which nearly 100 people died. As a result of this, young people demonstrating today recognize the legacy of the Red Shirts and commemorate their sacrifice.

The protesters also associate their battle with the People's Party of 1932, from which they take their name: People's Party 2. With the choice of a deliberately provocative name, they suggest that the transition from absolutism to constitutionalism remains incomplete in Thailand, proposing themselves as agents of an epochal change.