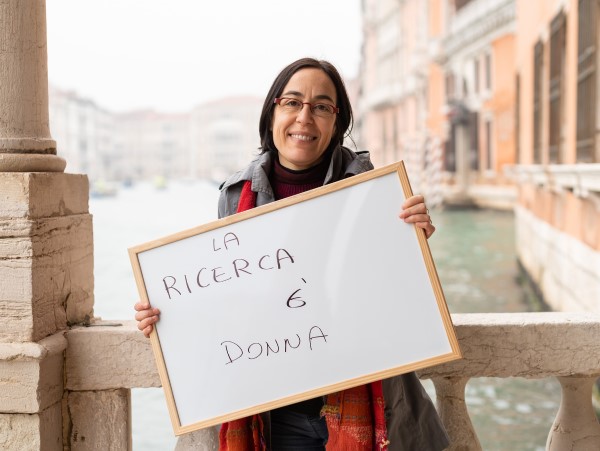

Maria Cristina Paciello, researcher at the Ca’ Foscari Department of Asian and North African Studies, investigates work dynamics in the context of neoliberal reforms and conflicts, focusing on the condition of women and young people in Arab countries.

Among other things, she has also served as scientific coordinator for the Institute of International Affairs in Rome, supervising projects like MEDREST and POWER2YOUTH.

She has a vast experience on the field, especially in places like Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia, but in her work, she analyzes the economic policies of all 22 Arab countries, including those in the Persian Gulf. In this specific area, gender equality is still a long way off and, in some countries, women are often denied basic human rights.

Why do we see so many discrepancies?

Because Islam is subjected to different interpretations and religion is not the only variable that influences gender dynamics in Arab countries. Islam intermingles with economic policies, which vary from state to state.

For instance, countries in the Gulf like Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the Emirates all have the lowest rates in the world for women in the workforce – 16%, 14% and 12% respectively, contrary to other Arab states like Morocco and Tunisia, where the rate of employment can reach 26%.

These particulars statistics are the result of intrinsic characteristics of the economic policy in the Gulf countries. Gulf economies rely on oil profits which, on average, make up for 35% of their GDP, with peaks of 47% in Saudi Arabia, but the petroleum industry employs very little labor. Moreover, these countries depend almost completely on foreign workers, mostly poorly paid Asians. About 80% of the workforce in the Gulf countries has been imported and this is why they don’t really need local women.

We should also keep in mind that we’re talking about the six richest Arab states, that contribute to over 50% of the GDP of the whole area. This economic prosperity allowed them to finance a generous public welfare system. Costs for families were cut down and, as a result, women have been discouraged from entering the job market.

Women are indeed present in domestic work, but they’re foreign and, what’s more, they must submit to the kafala system, which confers absolute rights to the employer, stripping the employee of every right, included the ability of going back to her own country.

Anyway, the existence of the kafala system cannot be exclusively attributed to cultural or religious components, but instead, it is more a result of the need of Gulf monarchies for improved stability and economic development.

After almost a decade from the Arab Spring, i.e. the revolts where numerous Arab nations fought for individual freedom and human rights, how has the condition of Arab women changed?

It has gotten worse, but the same goes for men. We’re observing three main trends: the strengthening of authoritarianisms, the increase in armed conflicts and the acceleration of those same economic policies responsible for the social crisis at the base of the revolts, like the public spending cuts and the privatization process.

Naturally, gender implications for these trends are different. For instance, they manifested into an upsurge of violence against women. Whether it’s during a conflict or in the presence of authoritarian governments, violence became a strategy to halt women’s participation to protests and send them back home. When it comes to work, the situation deteriorated for everyone, but it has affected women more.

Regardless of the harsher ways employed in repressing the revolts, women keep mobilizing in different ways, both in public and virtual spaces, for gender equality but also for political and social rights.

I’ll give you the example of Morocco where, since 2007, women have united in the Soulaliyate movement, fighting for the right to just compensation for the dispossession of collective land sold to privates.

In the South East of the country, in the village of Imiter, men and women are protesting against the metallurgic industry, which pollutes the environment and constantly disregards workers’ rights

Under particularly repressive regimes, women activism mainly manifests through online initiatives and campaigns, much like the one 32-year-old Manal al-Sharif launched in May 2011 to claim women’s right to drive, receiving enormous support both in the Arab region and outside. Her petition managed to push the Saudi monarchy to act in this regard.

Could you give us some updated statistics on women in the workforce?

The average rates of employment for women in the region are very low, among the lowest in the world – about 20%. We need to keep in mind that the data, as I’ve already mentioned, doesn’t account for the differences between countries and it only concerns formal work. Arab women – except in Gulf countries – are increasingly present in the informal economy, in precarious jobs and with no contract. With the increase in poverty and the decrease in purchasing power, many women have been forced to accept any kind of job.

The public sector – administration, education and healthcare – employs the most women. In the 50s and 60s, Arab governments implemented more generous policies, hiring young high school and university graduates, regardless of their gender. This was part of a state-centered development model, which lasted up until the mid-80s when, following the end of the oil boom, public spending underwent serious cuts to face huge debts with international creditors. From then on, governments stopped hiring and started firing people. Educated women are the most affected category when it comes to unemployment.

At the same time, with trade liberalizations and foreign investments, some Arab countries like Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt and Jordan have seen a steady increase of female labor in two export industries: manufactory (clothing) and agribusiness. Poor, illiterate women work in harsh conditions and for very little money, like for instance in the Moroccan region of Souss Massa, an area specialized in strawberry and tomato picking.

Starting from the 80s, these specialized cultivations made for the international market damaged the local production in some rural regions. Small farmers, no longer competitive on the market, were forced to sell their lands and emigrate. Consequently, the active population in these areas became almost exclusively female, those who worked to sustain their families now find themselves in a position where they have to accept dramatic work conditions in food farming supply chains.

Who buys the products made by Arab women? What countries import the most and at what cost?

Tunisia and Morocco export 90% of their farm produce and clothing items to the European Union– as a consequence, their economies are strictly dependent on Europe. From the 80s and mid-90s, thanks to a number of Euro-Mediterranean free trade agreements, an increasingly large number of European manufacturing companies started relocating production in these two countries. The convenience of this relocation resided in their geographic proximity and their low labor cost, which is necessary for any industry that wants to remain flexible and on-trend, while delivering medium quality items for a very low price.

Big European corporations control the whole manufacturing process and they supply Moroccan and Tunisian local factories with raw materials, i.e. the fabrics. These local factories, operating in the formal economy, sew the items and ship them back to Europe where they will be sold.

Over time, the competition became increasingly tougher and, in an effort to further shrink their prices, local factories had to subcontract smaller factories, that operate in the informal economy. In turn, these smaller factories relocated part of their work to micro-factories. As we gradually climb down this pyramid, work conditions get increasingly worse, as do the salaries.

The power imbalance between Arab countries and the EU is also evident if we look at the food industry. Morocco and Tunisia can export fruit and vegetables to Europe only from October to April, a period of time when they don’t risk competing with European farmers but at the same time they satisfy the trend of consuming certain types of produce in every season of the year.

This operation requires an intensive use of greenhouses and a larger number of workers. Seeds, pesticides and fertilizers are expensive, so once again, labor costs are the only variable that can be subjected to cuts.

Once again, European corporations are the ones in the control of the process and they act through a small group of local companies and landowners, who often have political backing by the government. Under these conditions, labor is mostly female.

You also deal with topics surrounding work and young people. In Italy, according to Istat statistics, the unemployment rate is well over 30%, double the European average. What is the situation like in Arab countries?

If we talk regional average, the unemployment rate for people in the 18 to 29-year-old age bracket is the same, about 30%. For young educated males it’s lower, about 23%, but on the other hand, educated women can reach a 48% unemployment rate. Besides unemployment, the real problem is the very low quality when it comes to work opportunities. Young people work with temporary contracts or even without any contract at all, in underpaid jobs, especially in tourism or customer care (if they’re educated) or as street vendors, when they don’t become bootleggers.

Young males tend to emigrate, while girls often go back to their homes and end up doing domestic work. Even in the Gulf countries, unemployment amongst young people started rising, so much so that it pushed governments to implement politics with the goal of nationalizing the workforce and substituting foreign workers with their own citizens.

The crisis in the Arab job market can be traced back to two key factors: young people are too many (almost 30% of the population) and they’re not prepared to face the needs of the market. These are both partial explanations and they offer a decontextualized interpretation of the economic and political dynamics in the Arab region during the last 30 years. The real problem resides in a growth model that proved incapable of diversifying the economies in Arab countries and, consequently, of employing educated workers.

As a matter of fact, open positions require cheap unqualified labor and offer awful working conditions. The responsibility in this case falls on the economic policies that were implemented starting from the mid-80s, which resulted in a privatization of public services and the introduction of foreign investments.

Investments that only concretely manifested, as I was saying before, in the oil industry, in the agribusiness and in the low-cost manufacturing industry.

Do you think Europeans are responsible consumers?

In Europe, responsible consumption is a rising trend. Having a certain awareness of the tie between our choices as consumers, the impact on the environment and the working conditions behind manufacturing is very important. What we really need, though, is to completely rethink our production-consumption systems and our trade relationships and to shift the focus to workers’ rights, environmental sustainability and social justice.

What we need to open the public debate on these issues are research projects that give a voice to marginalized communities. I have taken part to EU funded research projects on Arab countries and I’m certain that research can strongly contribute to the creation of ‘virtuous cycles’ and to the implementation of more equitable and inclusive policies.

Have you ever noticed any gender inequalities in the academic field?

Luckily, I’ve never encountered them in my path. My opinion is that the most urgent matter at hand is the precarious condition of many Italian researchers, both men and women.