Joseph Sanzo is from the US, but arrived at Ca’ Foscari in 2020 from the University of Warwick in the UK. He currently teaches at the Department of Asian and North Africa Studies where he is the PI of a prestigious ERC project, which is now in its final stages.

His study bridges the study of late antique magic in the Mediterranean and Near Eastern worlds (III-VIII cent. CE) with the study of early Jewish-Christian relations providing a comparative analysis of ancient magical texts and objects of Jewish and Christian origin (e.g. amulets, incantation bowls).

We asked him to tell us about the results of his research and how he approached this topic

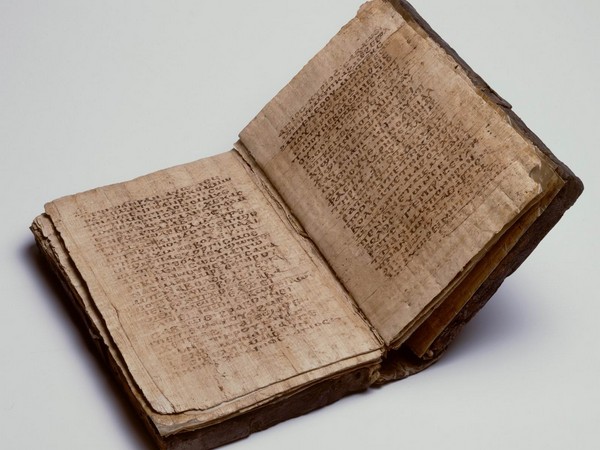

My project, Early Jewish and Christian Magical Traditions in Comparison and Contact (EJCM, ERC Starting Grant 2020–2025; no. 851466), contributes to the study of late antiquity by providing a detailed, comparative analysis of the similarities, differences, and contacts within and between early Jewish and Christian magical traditions on both the local and global levels. The primary sources for this project consist of Greek and Coptic amulets and grimoires as well as incantation bowls (inscribed in Jewish Babylonian and Syriac) that date from approximately the third century to the eighth century CE. The project focuses on four themes that are relatively common on these objects: (1) the uses of biblical texts and traditions; (2) the uses of sacred names and titles; and (3) the juxtapositions of words, images, and materials; and (4) references to harmful or illicit rituals. It also grapples with the relationship between literary and material evidence as it relates to quotidian rituals for healing, protection from demons, and cursing. Consequently, this project will not only include close readings of magical texts (written in the Greek, Coptic, Latin, Syriac, and Jewish Babylonian Aramaic [JBA] languages/scripts), but it will also place such magical materials into dialogue with select literary and legal traditions (e.g., patristic writings; Talmudic literature; Roman imperial legislation), which describe, resemble, or criticize the Christian and Jewish uses of magic or early Jewish-Christian relations more generally.

The members of the project adopt an interdisciplinary, interpretive framework for understanding the magical objects – and their operative social contexts – that is informed by recent scholarship on: the intersection of text, image, and material of magical objects; inter-religious contact and exchange (e.g., syncretism, foreignness/exoticism, boundaries, and identity); and comparison and classification in the study of antiquity (e.g., how to approach terms, such as magic, Judaism, Christianity). On both evidentiary and methodological levels, therefore, this project bridges materials, texts, and approaches that are usually treated independent of one another.

This project has its origins in large part from an essay that I wrote on ancient magic and early Jewish-Christian relations. Having been fully emersed in both fields of study, I noticed that the amulets that bolster ritual efficacy by using accusations of Jewish violence against Jesus had fallen between disciplinary cracks: that is to say, scholars who had focused on early Jewish-Christian relations and, therefore, were quite attuned to such anti-Jewish invective, typically did not investigate so-called magical objects, while scholars of ancient magic had glossed over such invective since it was not at the forefront of their research interests.

You are scholar of early Christian history. Why are magical objects such as amulets and grimoires crucial to the study of early Christian history, especially in lived contexts? Can you provide an example?

The so-called magical objects from Christian antiquity can help us recalibrate how we might think about early Christian boundary demarcation more generally. For instance, many scholars today have adopted an elite-vs.-non-elite view of religious and ritual boundaries, in which ostensible “elites” are seen as having a keen interest in distinguishing insiders from outsiders while “non-elites” are thought to have not appreciated such boundaries and differences. The Christian amulets and handbooks, which are often erroneously presented as evidence for such non-elite religiosity, challenge this model since many of these objects were quite interested in constructing religious and ritual boundaries, highlighting the differences between Christians and Jews, on the one hand, and between proper ritual practice and improper ritual practice, on the other. A good example is P. Leiden, Ms. AMS 9, a Coptic magical handbook that dates somewhere between the sixth and eighth centuries CE. The texts in this handbook not merely blame the Jews for persecuting and killing Jesus, but even compare them with a “dead dog” (ouhor etmoout)–slanderous language that resonates with the sentiments of some late antique patristic writers such as John Chrysostom. This same handbook, which includes a text that the practitioner calls an amulet (phylaktērion), also attacks and condemns other practitioners and their rituals using the same forms of invective that ecclesiastical leaders would have used against it (e.g., the practices come from foreigners, they are demonic/satanic in character, and they are harmful). What such objects demonstrate is that practitioners, who cut across diverse social strata, were highly interested in policing the boundaries between Christians and Jews as well as between what we might call “religion” and “magic.”

I should also add that these objects also offer interesting insight into the history of biblical reading, underscoring what we might call a “sensory” approach to the Bible in late antiquity.

What do you mean be a “sensory” oriented way of looking at biblical reception?

There has been recent work in the study of lived religion that has highlighted the diverse ways that human bodies interacted with material objects. This scholarly tradition provides a useful analytical lens through which we might reflect on how the material properties and characteristics of magical objects could have required people to engage with the biblical traditions differently across a range of senses. For instance, a series of late antique silver armbands with biblical scenes drawn and a portion of Psalm 91 inscribed onto their medallions not only necessitated the experience of the Bible on visual and aural/oral levels (the text was probably read aloud), but also on a tactile level (i.e., the wearer also had to rotate the armband to see all its scenes and to read the entire text). Furthermore, the silver material would have exerted itself on the human body in different ways depending on the ambient temperature (i.e., the silver would have felt differently on a cold day than on a hot day).

Papyrus and parchment amulets, which were typically designed to be worn on the body, would have facilitated even different ways of encountering the biblical text. The practitioner behind one early seventh-century CE parchment amulet that was cut into fifteen octagons (P.Oxy. 8.1077) inscribed portions of Matthew 4:23–24 into a series of cross-shaped patterns. This way of writing the biblical text not only connected the cross tradition with a healing text from the Gospel of Matthew on a visual level but would have required the client to sign the cross with his/her head in order to read the biblical text. Similarly, other papyrus and parchment amulets include crosses at the beginning of their texts in ways that suggest that the reader was being instructed to sign the cross before encountering the biblical material. In addition, a hematite pendant amulet emphasizes the story of Jesus healing the woman with a blood disorder through a drawing of the scene and a modified quotation of the story from Mark 5:25–34. The use of hematite almost certainly supported the biblical story on a material level, as hematite (also known as “bloodstone”) was widely believed in antiquity to have blood-staunching qualities. In sum, the magical evidence demonstrates the great degree to which biblical reading could involve the body and invoke diverse Christian traditions on textual, visual, material, and gestural levels.

Your new book, Ritual Boundaries: Magic and Differentiation in Late Antique Christianity, has recently been published by the University of California Press. What is the image on the cover?

The image on the cover is the obverse of a jasper gem with an inscribed drawing of the crucified Jesus. Around the image of Jesus, the carver inscribed various words, including: “O Son, Father, Jesus Christ”; the seven Greek vowels; and a misspelling of artanē (“suspension[-beam/rope]”). On the reverse of the gem, there are other inscribed words (e.g., Iōe; a version of Emmanuel; and variants of known magical words, such as [I]adatophōth and [A]straperkmēph). This gem is important to highlight for several reasons. First and foremost, there is a consensus among scholars that this gem preserves the earliest known depiction of the crucified Jesus in existence (the gem probably dates to the late second or early third century CE). I argue in the book that this gem’s early date and its visual emphasis on the suffering of Jesus make it likely that Jesus is not being invoked here as a triumphal god, but as one of the restless dead (on account of his violent death). The tradition that those who had died violently, prematurely, or without proper burial could be manipulated for ritual purposes was ubiquitous in antiquity, finding its way into various literary sources and magical handbooks.

This gem’s emphasis on the crucifixion also makes it a potent symbol for the concerns of the book more generally. The crucifixion and related symbols (e.g., crosses and Christograms) are among the most common motifs in early Christian magical traditions and, therefore, play an important role in the book. While some objects might simply include a cross or a reference to Jesus’s words on the cross (e.g., Eloi, Eloi, Lama Sabachthani), others focus on the crucifixion to a much greater degree. For instance, in contrast to the gem on the cover of the book, a seventh-century Coptic for exorcism (Brit. Lib. Or. 6796(4), 6796) creatively engages with the crucifixion in multiple ways: he cites a prayer that Jesus is supposed to have said on the cross, which mixes materials from the canonical gospels and magical traditions; he includes a conversation between the crucified Jesus and a “unicorn” (papitap nouōt); and he incorporates a drawing of the crucifixion scene into this spell, which places images of the crucified Jesus next to the two criminals, who are labeled Gēstas and Dēmas (as part of a shared tradition with the Gospel of Nicodemus). Other amulets highlight the crucifixion as part of a citation of a creed or as part of their anti-Jewish invective (as I’ve already noted above). In short, both I and the publisher thought that this jasper gem was a fitting image for the book.

The entirety of Joseph E. Sanzo’s new book, Ritual Boundaries, can be downloaded for free through the University of California Press (Luminos) website