According to the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger, 250 languages have disappeared in recent years and 3,000 are currently endangered. When a language dies, a conception and a worldview disappear forever. This is what is happening to the Dunan spoken in Yonaguni, a small Japanese island off the coast of Taiwan, inhabited by a thousand people, where there is no work, no high school, no future. Of the people left behind, only a few still speak Dunan, a language officially declared to be in great danger of extinction: it risks ceasing to exist within a generation, as families leave the island and the elderly pass away.

The project L’Isola, by artists Anush Hamzehian and Vittorio Mortarotti, aims to collect the last remnants of this disappearing community, which buries its dead in large tombs reminiscent of a mother's womb and relies on yuta priestesses, who are able to communicate with the spirits of their ancestors. The project consists of a sound installation, an audio-video installation and the publication of two volumes, an artbook, L'Isola, and a Dunan-English dictionary. The project was supported by Fotografia Europea and CAP - Centre d'art de Saint-Fons (France) in collaboration with the Department of Asian and Mediterranean African Studies at Ca' Foscari. L’Isola will be exhibited at the 16th Festival of European Photography in Reggio Emilia.

In particular, the artists collaborated with Professor Patrick Heinrich, who accompanied them to Yonaguni several times over three years. He also edited academic essays for the exhibition catalogue and involved LICAAM students in the translation of legends, myths and songs from Yonaguni Island. We have interviewed him about his collaboration with the artists and with the students.

How was Yonaguni chosen? How did this island inspire this project? What kind of landscape are we looking at?

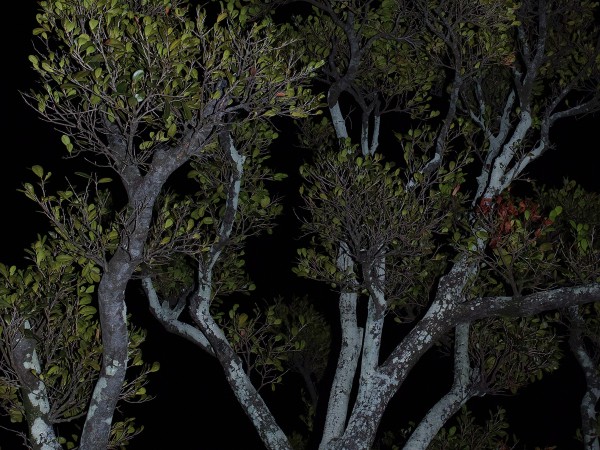

Vittorio Mortarotti and Anush Hamzehian, the two artists with whom I collaborated, wanted to tell the story of a language that disappears. They were interested in what lies behind a banal statement such as “a language disappears”. They thought that this could best be explored on a small island. I had been to Yonaguni many times before. The island is isolated, and its language is amongst those most endangered by extinction in Japan. As visual artists, Vittorio and Anush better understand what Yonaguni looks like. They say that Yonaguni is dark, and that it looks a bit like Scotland. The sky is often gray and threatening, but when you take a closer look, you notice the tropical vegetation and a population that walks with the relaxedness that is typical of the south. The list of things to be noted in the landscape is long. There is the ocean, wild horses that roam around freely, large numbers of abandoned houses, a forest that looks like a miniature version of the Amazon, two lighthouses at either end of the island and a military base.

You accompanied the artists to Yonaguni for three years. What was it like to have art and linguistic research work together? What was your experience as a researcher and mediator in this context?

I was surprised at how their project stayed open to changes and in a state of flux until the very last second. I guess Vittorio and Anush were surprised at how much one could learn about Yonaguni, but also at how little the others and I ultimately knew. Sometimes there simply was no knowledge present anymore. Our collaboration changed over time. They got to know more and more people from Yonaguni and worked with translators or learned to communicate directly with people of Yonaguni. We spent many evenings together eating local food or drinking beer on deserted beaches at night, looking at the stars. We learned that we were engaged in similar activities. I used social science methods to understand sociolinguistic and cultural changes, they used film, photos and sound recordings to do this.

Can you give us some examples of the Dunan dialect? What is its specificity? What can we discover about this community through language?

Dunan is one of eight languages in the Japonic language family. There are many features that are unique to Dunan. Its sounds are distinct, and so are its grammar and its words. If you want to say “where are you going” in Japanese, you say doko-e iku-no? In Dunan, the equivalent would be nma-nki hiru-nga? The word order of Japanese and Dunan is the same, and both languages use particles such as e or no in Japanese or nki and nga in Dunan for similar grammatical functions. However, the words and morphemes are obviously different, and so is their sound-structure. You can learn a lot about Yonaguni through its language. For example, Dunan has one word, dama, to express both mountain and forest, because there is only forest on the two mountains of the island. Hence, there is no need to distinguish between the two. It’s the same! To give you another example, while I was collecting my first documentation, I asked a consultant to introduce herself in Dunan. She was puzzled. Self-introduction is a nonsensical activity in Dunan, because everybody knows each other. Every language is the product of its sociocultural and geographic environment. Vittorio and Anush understood this from the start.