The dire humanitarian situation in Gaza rekindled the debate on the role of humanitarian intervention during conflicts and the paralysis of humanitarian diplomacy in protecting civilians. In April, seven aid workers of World Central Kitchen were killed while distributing food, and it was not an isolated case. Some 200 humanitarian workers, including 180 UN employees, have been killed in Gaza and the West Bank since last October. Continued interference in aid distribution in Gaza, dictated by the political agenda, has driven the civilian population to the brink.

Actors in the region, including the Gulf states, have been critical of the conflict from the start, but they have limited room for manoeuvre because of US support to Israel. Their engagement, however, has manifested itself in cohesive diplomatic pressure and increased resources to allow humanitarian aid into Gaza.

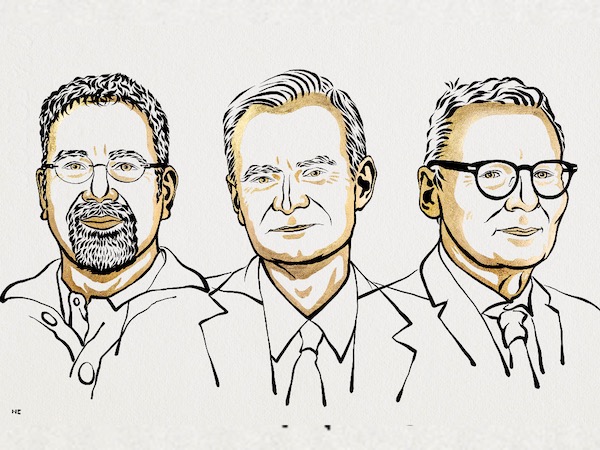

We discussed the topic with Altea Pericoli, Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Center for Advanced Middle Eastern Studies at Lund University, in Sweden, and from September 2025 Marie-Curie Global Fellow at Ca' Foscari University and Princeton University within the project ISLAMICAID - Aid from Islamic Donors in conflict zones. This project, supervised by Professor Matteo Legrenzi, aims to provide a broader understanding of the role of Islamic actors and Gulf States in humanitarian aid in conflict zones.

What was the situation of aid to Gaza before 7 October?

Regarding humanitarian aid, three factors make Gaza‘s situation exceptional.

The first factor is geographical: since 2007, when Hamas took power, the borders of the Gaza Strip have been under total Israeli control. Two of the only three crossings that allow the entry and exit of goods and/or people are in the south (Rafah and Karem Shalom), and one for the crossing of people only is in the north (Erez).

Then there is the political issue: Hamas, as the de facto authority governing Gaza, has been boycotted from the outset by players such as the United States and the European Union, and consequently, the United Nations has coordinated aid according to a policy of 'non-contact' with the group and organisations linked to it.

A third factor concerns the type of interventions implemented in the Gaza Strip, predominantly long-term humanitarian aid. On the one hand, this has been an essential tool for the population's sustenance, but it has also prevented the development of economic and social conditions. 81.5% of the population lives below the poverty line, 80% are dependent on humanitarian aid, and 47% are unemployed.

Humanitarian aid is crucial, offering assistance in emergencies to any civilian population affected by natural or man-made disasters. It should, however, be a short or medium-term response, accompanied by effective political strategies tackling structural deficiencies and integrating long-term development objectives.

In her book 'The Political Economy of Aid in Palestine', development economist Sahar Taghdisi-Rad openly criticised the “charitable” drift of humanitarian aid in Gaza, inducing aid dependency and never leading to a radical improvement in the economic conditions of the population: “When disbursed in the context of conflict and violence, aid becomes an inevitable part of that context; hence, its effects on conflict do not remain neutral”, despite what most of the donors claim. As Taghdisi-Rad reminds us, humanitarian aid is always intertwined with political developments. In Gaza, for example, assistance has followed the logic and policies of donors in a way that appears disconnected from the context and all the structural shortcomings caused by the occupation and internal political incapacity. However, responsibility should not be placed on the humanitarian interventions implemented so far.

What happened after 7 October?

Against this picture of the aid situation before 7 October, the current circumstances and the distribution of humanitarian aid during the conflict need further consideration. The entry of assistance since the start of hostilities has been linked to negotiations between Hamas and Israel on the release of hostages and the ceasefire. The entry of basic necessities has thus been subjugated to politics, in violation of international humanitarian law. The number of humanitarian convoys between January and February 2024 averaged between 100 and 200 per day, whereas before the crisis the average daily number was 500 per day, including fuel. Moreover, this aid enters through the Rafah and Karem Shalom crossing in the south and hardly makes it to the north of the Strip. At the beginning of April, the Erez crossing was opened for the first time to allow aid to enter north Gaza. Furthermore, the difficulties and lack of safety in the aid distribution led some organisations, including WCK and Anera, to suspend their activities in Gaza.

How important are the regional actors?

As mentioned, from a donor perspective, an influential group of actors operates in the current crises, especially in the MENA region, in the same contexts as Western donors, including Gaza: the Gulf States. In this case, it is very interesting to look at these actors from the perspective of their role in mediating and supporting aid in the current crisis.

Qatar is in a 'privileged' position due to its relations with Hamas, also considering that part of the movement's leadership has been in Doha since 2012. Qatar has become crucial in mediation and humanitarian diplomacy and has always been one of Gaza's most important Gulf donors. In 2021, it allocated $310.5 million for aid in Gaza and the West Bank alone.