Last 13 January's elections turned the spotlight on Taiwan and its delicate geopolitical situation. The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) won a third consecutive term. Lai Ching-te, the outgoing vice-president also known as William Lai, was elected president. He has been a strong supporter of independence from China in the past, but used moderate tones in his victory speech, in line with the cautious attitude that has characterised Taiwan in recent years.

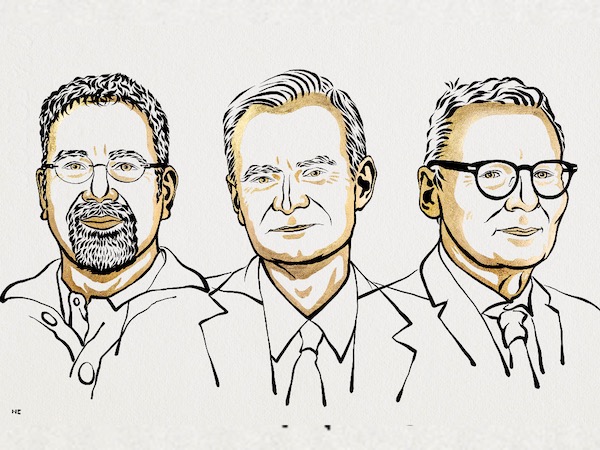

To learn more about the situation in Taiwan, we spoke with Professor Renzo Cavalieri, Professor of Chinese Law at the Department of Asian and North African Studies at Ca' Foscari.

Professor Cavalieri, why can't Taiwan be considered a state?

We cannot understand the situation in Taiwan unless we consider it from a historical perspective. It all started with the Chinese Revolution and the separation between the People's Republic of China (PRC), which came into being on 1 October 1949, and the government of the former Republic of China (ROC) of the Kuomintang (Guomindang) party, led by Chiang Kai-shek. Chiang Kai-shek, a few years before 1949, went into exile on the island of Formosa, i.e. Taiwan, and 3 million people with him. A veritable exodus.

This is the 1950s, during the Cold War. Taiwan enjoys the support of the United States and becomes the outpost of the West against the communist bloc, acquiring its own political stand vs. mainland China. It must also be remembered that previously, from the late 19th century until the end of World War II, Taiwan had been under Japanese occupation. Japan’s imprint profoundly changed the island’s socio-economic structure and set it along a different path from that of China. For a long time, the Republic of China in Taiwan was internationally recognised as the legitimate Chinese government, in lieu of what was initially described as a 'communist rebellion temporarily occupying the rest of the country'. Then, as the years passed and the Communist Party's power grew stronger and more stable on Chinese territory, it became clear that China's government was no longer in Taiwan. In the 1970s, most of the world's countries interrupted diplomatic relations with Taipei, i.e. the representative of pre-revolutionary nationalist China, and established new ties with Beijing: it was not possible to maintain relations with two governments that claimed to represent the same sovereign state. In 1971, the Chinese seat at the United Nations also passed to Beijing. Beijing has always regarded Taiwan as a province that would sooner or later be reannexed to the People's Republic, but up to Xi Jinping the attitude towards Taiwan was very pragmatic and cooperative, so much so that economic relations and direct investment have grown exponentially. The situation has changed dramatically under Xi's presidency, especially in recent years, also due to the deterioration of the global geopolitical scenario.

Taiwan is therefore in weird spot, internationally: it is indeed a state, but the Republic of China cannot be recognised as such. Only 12 small countries maintain official diplomatic relations with the Republic of China, and as a consequence have none with Beijing. On the other hand, severing the umbilical cord binding Taiwan to China does not seem to be a viable option, first of all because of weak internal consensus, and above all because it would mean unleashing Beijing's reaction, with unpredictable consequences. However, in the 'consciousness' of Taiwanese citizens, sovereignty and statehood are not in question, but the difference between the island and the mainland is increasingly clear.

Taiwan is a key economic and commercial actor, so how does it manage international relations from this point of view?

A series of bilateral and multilateral agreements serving a wide variety of purposes are used to enable political, economic and cultural relations with ROC. Several countries, including Italy and most European countries, maintain non-diplomatic bilateral relations through de facto embassies, called Economic, Trade and Cultural Offices or Representative Offices. Taiwan is also a member of various international organisations, in which the People's Republic of China is generally also present, such as the Olympic Committee or the World Trade Organisation, under the aptly ambiguous name of 'Chinese Taipei’.

How come these 12 small countries, including the Holy See, recognise ROC as a state? What benefit do they derive from this?

We are talking about a few countries in Central and South America (Guatemala, Paraguay, Belize) and small Caribbean or Pacific islands that are fairly irrelevant on a global level. The Holy See is in their midst for historical and ideological reasons: it is in conflict with Beijing over freedom of worship and the consecration of bishops, while Beijing does not accept the Pope's sovereignty over its national Church. For the other countries on the list the motivation is largely economic. Taiwan has invested in infrastructure in the islands and in Central and South America; in recent years, however, China has also started to invest in these small counties and the number of supporters of ROC has gradually decreased: as recently as 2021, Nicaragua abandoned Taipei for Beijing.

What do you think will happen in the near future: the reunification desired by the People's Republic of China or will Taiwan become an independent state, internationally recognised?

The current government of Xi Jinping considers Taiwan as an integral part of Chinese territory. In China there is a very strong rhetoric of inevitable reunification, which has now become a slogan: 'reunification is the glorious national destiny'.

But Taiwan’s reunification is not easy, first of all because the Taiwanese (as the election results reveal) do not appear to be attracted by the idea of being part of the Chinese empire. Taiwan has been on a path of democratisation since 1987, and this has made its position increasingly problematic for Beijing. The Kuomintang was the rival party to the Communist party, but did not question the assumption of China as a unified country. The rise of the Progressive Democratic Party, on the other hand, increased fears of a turn towards formal independence.

In the early 1990s, China and Taiwan had reached a de facto compromise: the Taiwanese would accept things as they were without questioning the principle of China being formally one country. This compromise remains in place for the time being. PRC’s government does not seem to have a concrete plan or timeline for unification, but it needs to subdue any push towards independence. China therefore applies constant military and also economic pressure - I am thinking of recent cases of tax investigations into Taiwanese companies' investments in China - in order to influence ROC’s political choices. The outcome of the elections confirmed the prevailing consensus on preserving this ambiguity. According to newly elected President Lai, there is no need to declare independence or change name, because Taiwan is in fact already a sovereign state. A pragmatic attitude, that does not dwell on the formal ideological issue.

How do you view the behaviour of Japan, the US or the EU? The Chinese government criticised their leaders for congratulating Lai and asked them to stay out of China's 'internal affairs'.

I think we could describe their attitude as ambiguous. Their aim is to preserve this peaceful balance, which was to everyone’s best interest so far: Taiwan is a strategic place both politically and economically. But having good relations with the People's Republic of China is also indispensable.

Japan is geographically close to Taiwan and maintains a very close relationship with it, also on a cultural level. I am thinking for example of the delicious Taiwanese cuisine, which is certainly Chinese but has strong Japanese influences.

US President Joe Biden reiterated that Washington does not support the island's independence, yet the US deal with Taipei, for all intents and purposes, as with a sovereign state. Moreover, in our time of geopolitical tensions, when it comes to security issues with China, Taiwan represents for the US an absolutely crucial square of the chessboard.

The EU has every interest in maintaining the status quo, too. Everyone's position is pretty homogeneous: preserve Taiwan's right to live as an entity independent from Beijing and, at the same time, respect the One China policy negotiated as back as in the 1970s by the US and Beijing.

There is talk of a 'silicon shield' protecting the island. When and how did Taiwan become the world's largest producer of semiconductors, the essential components of all digital products, devices and infrastructure?

Taiwan is one of the so-called 'Asian tigers', together with Singapore or Malaysia, which emerged as important industrial powers around the 1980s. The productive Sino-Japanese mix, the Confucian tradition of hard work, an efficient government, and also the privileged relationship with the United States certainly played a role. Many Taiwanese engineers have studied in the USA, and North America strategically and massively supported Taiwan’s public and private investments in technology. Over the years, various industrial policies aimed at increasing national competitiveness have also been adopted. One example is that of industrial parks, which have greatly favoured the development of the semiconductor sector in particular.

The success has been extraordinary and today Taiwan produces almost 60% of the word’s chips. This near-monopoly on one of the world's most valuable goods makes Taiwan an even more desirable, and yet delicate, stakeholder.

Let us return to the election results. How is it that William Lai won the elections, but does not have a majority in parliament?

William Lai, outgoing Vice-President, won the presidential election with 40% of the vote, but his Democratic Progressive Party did not have a majority in the legislative elections, so Lai will have to make deals and find common ground with the other two parties in parliament: the Kuomintang, which won a majority of seats, and the People's Party, which will act as a sort of balance of power. We shall see. Bear in mind that we have been discussing Taiwan's politics in the light of its relations with Beijing only, but the election campaign was conducted, as in any other democratic country, around multiple issues. Topics such as energy, labour, or the minimum wage were all relevant in the programmes, and will conspicuously influence any parliamentary alliance.

And as for Lai's foreign strategy, it will be to maintain the status quo, the 'let sleeping dogs lie', and this position is also shared by the other political forces.

Do you see potential risks to maintaining this status quo?

Everybody, including the Chinese government, seem to accept this ambiguity. This is reflected in the bland statements made by Beijing after the elections. In theory, the pragmatic approach suits everyone. The only risk I see is that, with the current international tensions, pragmatism may be overtaken by ideology, especially if the PRC government decides to take concrete action to realise what it sees as the historic task of national reunification. However, maintaining the balance achieved on the Taiwan issue will, above all, depend on new developments in global relations.